Junk City

“Architecture disappeared in the twentieth century”, writes Rem Koolhaas in the opening paragraph of Junkspace (2001)1. It was replaced, he continues, by Junkspace — a kind of built environment that isn’t really designed but kind of just happens when you throw together a load of drywall, prefab concrete slabs, venture capital, air-conditioning, elevators, and vinyl stickers and hot-glue everything into the shape of an office complex. Koolhaas sees in this not an abberation, but the dominant form of contemporary building, “the essence, the main thing”.

Construction on Garden House, the RCA’s temporary White City campus, began in 20012 — the same year Koolhaas’ text was first published in the Harvard Guide to Shopping. Based on the timeliness of its publication, and the fact that it manages to put into words all the dread this building induces in me, I propose Junkspace as the unofficial companion essay to RCA White City; RCA White City as the companion building to Junkspace.

Endless Space

Continuity is the essence of Junkspace

In a text published a few decades earlier3, Koolhaas describes how electricity, elevators, and air conditioning moved from the magic shows, rides, illusions, and scams of Coney Island (where they orginated) into Manhatten in the 1870s, where they allowed the endless, upward expansion of the skyscraper. Junkspace, writes Koolhaas, relies on the same set of technologies, but expansion now happens in every direction, all at once, for its own sake:

Continuity is the essence of Junkspace, it exploits any invention that enables expansion, deploys the infrastructure of seamlessness: escalator, air-conditioning, sprinkler, fire shutter, hot-air curtain … It is always interior, so extensive that you rarely perceive limits; it promotes disorientation by any means [...]

Consider Garden House: Three virtually endless corridors stacked on top of each other, plus a lobby. There is no discernible reason that the building should end where it does — maybe it’s just where the money ran out. The rows of desks may as well continue in all three directions forever, supplied with filtered air, light and electricity through service lines running behind plastic tiles above and below.

But Garden House is also part of a much larger junkspace, ever metastasizing: The back door opens into a paved garden, which leads into a second, larger stack of corridors, which leads into a miniature strip-mall of fake regional restaurants, followed by a kind of parade ground patrolled by men in purple corporate uniforms4. The Junk-Mothership (Westfield) looms just a few minutes down the road.

Conditional Space

Transparency only reveals everything in which you cannot partake

Because it costs money, is no longer free, [air]conditioned space inevitably becomes conditional space; sooner or later all conditional space turns into Junkspace.

RCA/CSM/CCA/LCC/LHR/LGW5 are conditional spaces: Pay for your immigration paperwork, ESL certificates, tuition and library fees, and you’re allowed past card readers and security guards into the building. Stop paying any of those, and your passport, access pass, and library card will be turned off remotely in a matter of hours.

When space becomes conditional, keeping out anyone who doesn’t fulfil the conditions becomes the primary objective. The ever-present cardreader (accepting visa, mastercard, amex, student id, visitor pass, and library card) may be the most obvious built manifestation of this. But there are countless other pieces of junk serving the same purpose: security desks, lobbies, sliding doors of various descriptions, cameras, frosted glass, numbering systems, reports, the student helper form (all visits must be transactional), sign-in sheets, visitor's passes.

When I invited two friends into the studio recently, it took the better part of an afternoon and corruption on multiple levels to get them past the security desk. Visitors are only tolerated for limited periods, alumni are only welcome with their credit cards clearly visible.

Temporary Space

Junkspace is additive, layered and lightweight, quartered the way a carcass is torn apart

Junkspace is temporary. The economics that compel electronics manufacturers to make sure your phone breaks after a couple of years apply to construction, as well. Like phones, these buildings are designed to be consumed, ditched, replaced, and re-consumed in short intervals.

Junkspace is additive, layered and lightweight, quartered the way a carcass is torn apart — individual chunks severed from a universal condition. There are no walls, only partitions, shimmering membranes frequently covered in mirror or gold […] Where once detailing suggested the coming together, possibly forever, of disparate materials, it is now a transient coupling, waiting to be undone, unscrewed, a temporary embrace with a high probability of separation; no longer the orchestrated encounter of difference, but the abrupt end of a system, a stalemate. […] While whole millenia worked in favor of permanence, axialities, relationships and proportion, the program of junkspace is escalation. Instead of development, it offers entropy.

Everything about Garden House is provisional: None of the interior walls are load-bearing, so they can be moved as market forces dictate. A Making Space can be turned into a Smart Zone overnight by applying a few vinyl stickers and replacing a couple of technicians (zero-hour contracts make that a simple operation). The heavy, hard-to-move equipment like printing presses and machine tooling is kept at other campuses, as if to prevent their material permanence rubbing off onto Garden House6. The whole place feels precarious, as if it may cease to exist at any moment.7

Consumed Space

Because it is endless, it always leaks somewhere in Junkspace

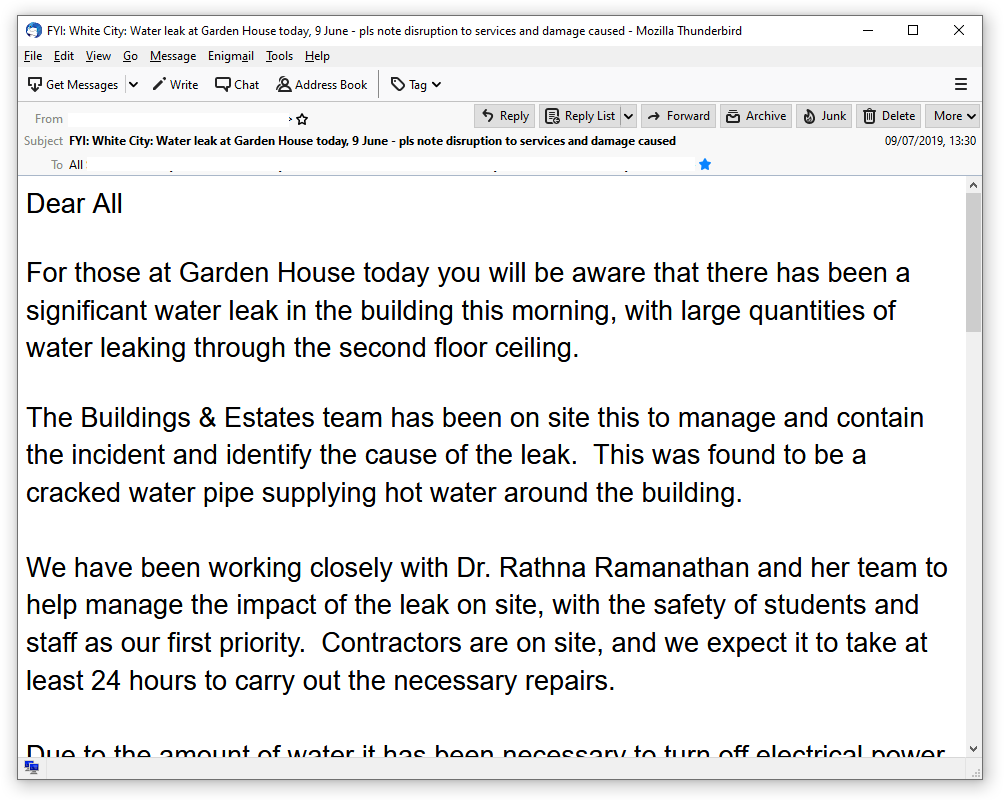

I’ve lost count of how many times the heating has been broken at Garden House. Electric heaters are scattered around the studio, artefacts of ice ages past. A constant state of disrepair is no accident, but a defining feature of Junkspace:

Because it is endless, it always leaks somewhere in Junkspace; in the worst case, monumental ashtrays catch intermittent drops in gray broth […] Because it is so intensely consumed, Junkspace is fanatically maintained, the night shift undoing the damage of the day shift in an endless Sisyphean replay. As you recover from Junkspace, Junkspace recovers from you: between 2 and 5am, yet another population, this one heartlessly casual and appreciably darker, is mopping, hoovering, sweeping, toweling, resupplying.

This endless recovery loop is mediated by a constant stream of language “woven through [Junkspace’s] texture of canned euphoria”. Your email account is probably full of it: Apology after apology (“Sorry for any inconvenience caused by the broken heating/clogged toilet/Prince of Wales”) from the Buildings and Estates department, mixed with the occasional threat to bin your belongings if not removed by such and such a date.

How to survive Junkspace

Public space is the space of transgression

Once you recognise that Garden House and its surroundings are Junkspace, the question becomes: What do you do? Koolhaas doesn’t help us here. To him, architecture has nowhere left to go except sideways “like a crab on LSD”.

Hal Foster gives us a partial response8, writing in 2013:

In times of transition artists have played critically with capitalist junk. In his manifold practice Merz, Kurt Schwitters turned bits of rubbish in post-World War I Germany — fragments of advertisements, cashiered tickets, odd items stolen from friends — into the stuff of collages and constructions. […] Other examples in this vein include the “Bunk” collages producd by Paolozzi out of American glossies in post-World War II England, as well as installations […] staged by Claes Oldenburg in The Street and The Store in the early 1960s. In the present, too, artists such as Isa Genzken, Thomas Hirschhorn, and Rachel Harrison excel in this practice of mimetic exacerbation. If there is no other side to Junkspace, indeed no outside at all, they are still able to find fissures within this world, to pressure these cracks, and open up a little running room.

In other words: If you can't dismantle Junkspace in the immediate term, you should subvert it. Find an opening somewhere, and carve out a space that is everything Junkspace is not: Dirty, uncontrolled, transgressive, economically useless. You build real communities within and without the ones imagined by the marketing department. Letting your friends in through the back door is an important act of architectural subversion, as is solidarity with the nightshift 9.

But the more hopeful point is this: Universities have the potential to be islands of crucial public space, even as consumerism turns the surrounding landscape into junk. Imagine what Garden House could be if tuition was free, cleaners, teachers, and technicians were on secure, long-term contracts, immigrants didn't have to fear deportation, and universities were funded such that they could build appropriate buildings without squeezing students for petty change at every turn. Perhaps we could dispense with the prison-style visitation system currently in place, and make the University once again a part of public space, and open to everyone10. That world needs to be our ultimate goal 11.

Rem Koolhaas (2001): Junkspace. In The Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping, Taschen. Available at cavvia.net/junkspace ↩︎

BBC (2004): BBC Media Village White City. Press Release. Available at [bbc.co.uk/pressoffice/pressreleases/stories/2004/05_may/11/media_village.pdf](http://www.bbc.co.uk/pressoffice/pressreleases/stories/2004/05_may/11/media_village.pdf ↩︎

Rem Koolhaas (1978): Delirious New York., Oxford University Press ↩︎

I assume those came when BBC Media Village was sold off to private developers in 2015. They quickly rebranded it to White City Place, a title so normcore it’s frankly impressive. BBC (2015): Media Centre, London: first in, last out. Available at bbc.co.uk/blogs/aboutthebbc/entries/abe09136-ed47-4083-b35d-03473ecf8e8e ↩︎

Royal College of Art, Central Saint Martins, Camberwell College of Arts, London College of Communication, London Heathrow, London Gatwick ↩︎

The next generation of temporary is around the corner: Troubadour Theatre is literally built from scaffolding and tarp. ↩︎

The notion of making everything temporary for the worker, flexible for the boss is part of a bigger economic trend. See: David Banks (2019): Against We. Commune Magazine, available at communemag.com/against-we/ ↩︎

Hal Foster (2013): Running Room. In Junkspace with Running Room, Notting Hill Editions. ↩︎

Sally Weale (2019): UCL workers to decide on strike action over “unjust” outsourcing. The Guardian, available at theguardian.com/education/2019/oct/09/ucl-workers-to-decide-on-strike-action-over-unjust-outsourcing ↩︎

I’m lifting the properties of “public space” and the caption to the final image from the architect Wim Cuyvers. His text Public Space (Undated) is available at readingdesign.org/public-space ↩︎

Roland Ross contributed notes to this piece. It appeared first in Content Full Issue 1. ↩︎